Success is sweet. Vera, Nikola, Lucija, Alexander, me

Success is sweet. Vera, Nikola, Lucija, Alexander, me

Rewritten in 2025. The original was influenced too much by a wannabe start-up mindest that had befallen me in 2019-2021

In 2019, towards the end of my Bachelor’s, I led an undergrad student research team for the iGEM competition. iGEM stands for international genetically engineered machine and aims to further biological research among students. I think it is a pretty great idea and it was a significant experience for me, both scientifically and personally.

In short

Our team iGEM NAWI Graz 2019 decided to a method for the early detection of American foulbrood (AFB), a severe bee disease. We delived the proof of principle for our project Beeosensor - a biosensor based on detection of the fouldbrood spores through highly specific binding by bacteriophages. We performed quite well, winning two awards and even being nominated for the Grand Prize. For scientific details, please go here; this post is dedicated to my personal experience.

The beginning

Science is great, especially when looking at it from outside. But since my mind had been set on doing science since about a decade at that point, just learning at some point wasn’t enough anymore. I wanted to do. And so I joined the iGEM team at my universities. In 2018 it didn’t work out because I took on a full time summer job, but in 2019 I had the time and comittment to make it work. I even became so comitted that I became team leader when the original team leader dropped out after the first months. That made the experience extra intense, as I took the job very seriously. Maybe even too seriously, but I had made a promise to my team and I would keep it.

My team

Some of my colleagues were especially eager to make a team video and so after a long time of planning and shooting scenes, we had produced this masterpiece:

You can find other teams' videos on youtube. In the end, they were shown at the conference in Boston and for me that moment felt quite significant. Many of the videos tell about the same difficulties that out team went through and with all the energy and emotions I had put into making this project succeed, I was rushed by a sudden feeling of community and shared experience.

The research

When I announced that I would be ready to undertake the task of the team leader, we were were still full of naive optimism and envisioned the prototype of the Beeosensor, fully functional, tested and ready until the end of the summer. The sky seemed blue, the roadmap clear. We were quite wrong. Tough lessons were taugth this summer.

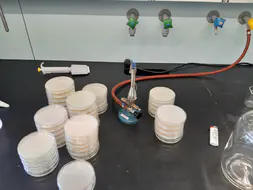

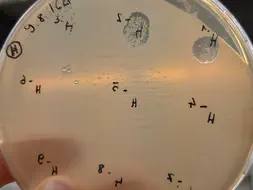

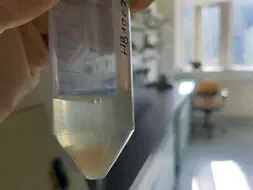

It was difficult to hold the team together, as formed relatively late, were very interdisciplinary, worked in three different labs (molecular, chemical, engineering) and not all members wanted to work full-time on our project. Problems creeped out of every corner, the tasks accumulated, and the optimism started to wear off, a core of members remained and others all but dropped out. An insufficient desinfection method led to contaminations of our bacterial cultures for weeks, the phages (bacteria-viruses) would not replicate and when they did, we had issues isolating them with the proposed method, necessary criteria for the competition almost were not met, and the financing was lacking behind the expectations.

It was tough.

However, our project did progress, in painfully slow steps and with much reduced goals. Proof of principle for the method instead of a fully functional prototype. But still. Proof of principle it was. We got our final and long-awaited results two days before the deadline. Talking to other groups we learned that many shared a similar story. Lab is hard. Especially for undergrads on a crammed timeline.

The congress

Our sole hope for the congress in Boston was a gold rating, essentially the best out of three ‘grades’. Half of the 80 other overgrads achieved that as well (some of our team were overgrad, but most were still umdergrad). The awards however are the real deal at iGEM. But with better financed teams from universities like MIT and Harvard, what chance did we have?

The following 30 minutes were some of the most unreal in my life.

We were first nominated for the best diagnostics project and we cheered … when we were announced the winners of the best diagnostics project we jumped up from our seats and celebrated and joked and laughed. We were nominated for best human practices. At that point it felt dreamy already. And then we won best human practices. There were no more sounds I could make to express my feelings appropriataly. We were shouting our lungs out. Very untypical for me, but there I did.

Months of hard work getting honored in such an umexpected way was an incredible experience. It was surreal, it felt a bit as if anything could become true with a snap of my fingers, manic, for a few minutes. We were then nominated for the best presentation, the best poster, and even for the Grand Prize, the actual winners of the competition. In that moment those nominations felt only logical, but of course, they were decent achivements in their own right (Proof).

Acknowledgements

Last, I want to thank the people who supported our team and helped us to make all of our achivements possible:

- Hannes Beims and Wolfgang Schühly, who were the main “intellectual contributors” and provided us with phages and bacteria.

- Peter Macheroux and Eda Mehmeti, who gave us access to two labs and access to the equipment necessary for our project.

- Marina Toplak, Julia Messenlehner, and the other members of the institute, who supported us troughout the project.

Without you, Beeosensor would not have been possible